Ever since I was a child, I’ve been a natural pessimist. I always expected the worst because, you see, the “worst” had already happened to me; when I was 11-years-old, my beloved dad, David, died of cancer.

Losing someone when you’re young is starkly different to losing them as an adult. It’s easier in some ways, harder in others. You don’t have the full gamut of emotions to have to contend with, yet you also don’t have any of the coping strategies that come with experience and maturity, nor the language to express that endless expanse of grief.

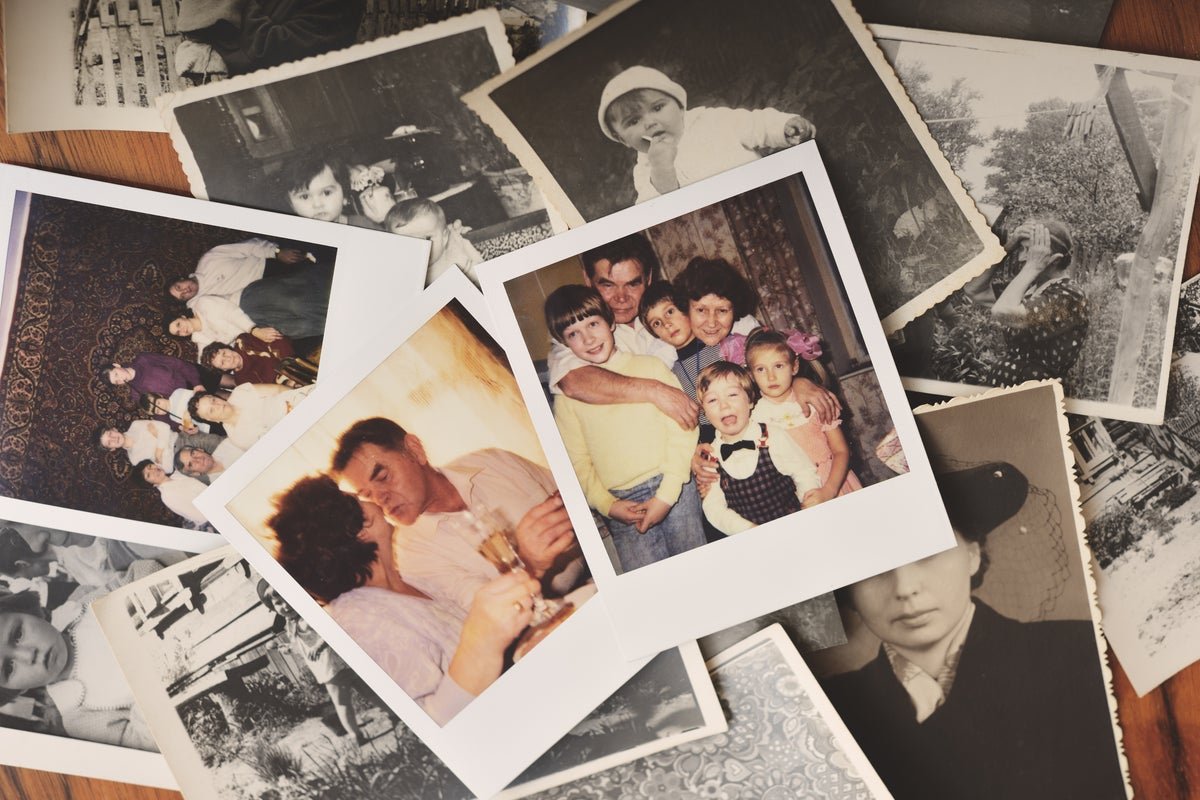

My excellent father was just 47 when he passed, an age that sounded old to me at the time but it now feels devastatingly young. He was the “fun” parent: the one who would bundle me and my sister to the floor and pretend to make us into pizzas, tickling us mercilessly to “knead” the dough; who would surprise us with macaroons from the supermarket on a Saturday morning; who would sing, loudly and proudly, while walking down the street within earshot of strangers, oblivious to our embarrassment.

We’d had, in theory, time to prepare for his death. He’d had bowel cancer once before, been treated successfully, gone into remission. But then it came back – much worse, much more aggressive. I have very few concrete memories of that fraught period, just the outlines of what must have been happening sketched in the lightest pencil. A freezer stocked with Calippo ice lollies to help with the mouth sores after chemo. Playing a game where we all imagined his white blood cells as knights on horseback, charging in and spearing the tumour with lances like they were in a medieval jousting tournament. The palpable desperation that hung in the air as my mum frantically attempted to rearrange his excursion to go up in a hot air balloon – dad’s lifelong dream and final bucket list item – after it was cancelled due to poor weather. Thankfully, it happened. That must have been quite near the end, I think.

I wasn’t a pessimist yet – because the worst hadn’t happened yet – and so I never for one second truly believed that he would die. I simply couldn’t fathom such an outrageous notion: not when he and my stoic, incredible mum sat us down and told us the cancer was terminal. Nor when they stopped treatment and he returned home. Nor when the nurse from the local hospice came to stay in his final days. Not even when she woke me in the middle of the night, told me gently it was time, and led me to the spare bedroom where the family gathered to say our goodbyes. Even as we felt dad’s spirit leave his body, still a part of me remained convinced it must be some kind of elaborate trick or ill-judged prank – that any second he’d spring up and say, “Ha! Gotcha!”. Because it couldn’t be happening, could it? Not to me. Not to my dad. My weird, wonderful, funny, darling dad.

We call this denial now, but all I knew then was that everything I believed to be true about the world also died in the same moment he did. Bad things could happen to good people, and they did, every day, with no rhyme or reason behind any of it.

So yes, since then, I’ve always expected the worst. But that hasn’t forged me into a depressing doom and gloom-monger. Quite the opposite. I like to think I’m one of the most positive people you’ll ever meet – because every time the worst doesn’t happen (and, most of the time, it really doesn’t), I’m beyond overjoyed, bubbling over with starry-eyed gratitude. Every good thing that comes to pass is a gift to be relished and appreciated – never, ever taken for granted.

Every good thing that comes to pass is a gift to be relished and appreciated – never, ever taken for granted

It’s shaped me in other ways, too. Those left behind – and there are millions of us – are part of an invisible yet mighty band of brothers. We’re battle-scarred and forever shaped by our loss, yes, but by the same token capable of the deepest empathy for others. Macmillan Cancer Support estimates there are almost 3.5 million people living with cancer in the UK. We must change how we support these people so we can reach everyone, especially those experiencing the worst cancer journeys and outcomes.

Why Macmillan Cancer Support Needs You

Almost one in two people in the UK will get cancer in their lifetime — but not everyone gets the same care.

Right now, factors like where you live, your income, ethnicity or other health conditions can affect how you’re diagnosed, treated and supported.

Macmillan Cancer Support is working to change that. By getting involved in a Coffee Morning, you’re helping make sure everyone with cancer gets the personalised care they need, no matter who they are or where they live.

It’s why sharing our stories and learning we’re not alone is so empowering, and why events like Macmillan Coffee Morning can help us find support – not just in terms of raising money to fund the vital work of Macmillan nurses and beyond, but to start a dialogue, open a conversation, and find out how others in our communities have also been touched by cancer.

“It seems to me, that if we love, we grieve,” as musician and artist Nick Cave once put it. “That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined.” And grief can be its own kind of superpower, too, one that transcends the impulse to run for the hills when faced with another’s pain and helps us to sit with them in their suffering. The worst might yet happen – but there’s meaning to be made from mourning, if only we look closely enough.

Find out how you can help raise vital funds by hosting a Macmillan Coffee Morning. Sign up now on the Macmillan website

Macmillan Cancer Support, registered charity in England and Wales (261017), Scotland (SC039907) and the Isle of Man (604). Also operating in Northern Ireland.

#learned #find #meaning #loss