BBC North American business correspondent

Keen

KeenIn a corner of Kentucky just outside of Louisville, family-owned shoe company Keen is opening a new factory this month.

The move fits neatly into the “America First” economic vision championed by the Trump administration – an emblem of hope for a manufacturing renaissance long promised but rarely realised.

Yet beneath the surface, Keen’s new factory tells a far more complicated story about what manufacturing in America really looks like today.

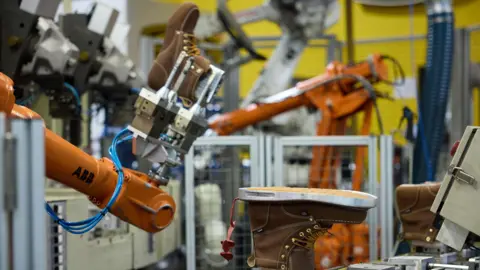

With just 24 employees on site, the factory relies heavily on automation -sophisticated robots that fuse soles and trim materials – underscoring a transformation in how goods are made today.

Manufacturing is no longer the labour-intensive engine of prosperity it once was, but a capital-heavy, high-tech enterprise.

“The labour rates here in the US are very expensive,” says Keen’s chief operating officer, Hari Perumal. Compared to factories in Asia, American staffing costs run roughly 10 to 12 times higher, he explains.

It’s a reality that forced Keen to come up with a solution back in 2010, when rising costs in China pushed the company to begin producing domestically – a decision which today offers it some buffer against Trump’s tariffs. But it’s far from a straightforward win.

Shoemaking, like many industries, remains tightly linked to sprawling global supply chains. The vast majority of footwear production is still carried out by hand in Asia, with billions of pairs imported annually into the US.

To make domestic production viable, Keen has invested heavily in automation, enabling the Kentucky plant to operate with just a fraction of the workforce required overseas.

“We are making products here in the USA very economically and very efficiently,” says Mr Perumal.

“And the way we do that is with tons of automation, and [it] also starts with how the products are designed and what kind of materials and automation we utilise.”

Keen

KeenThe challenges of reshoring manufacturing go beyond Keen. Major brands such as Nike, Adidas, and Under Armour also attempted to develop new manufacturing technologies in the US around a decade ago — efforts that ultimately failed.

Even Keen only assembles 9% of its shoes in America. It turns out that making shoes in a new way, and at scale, is complex and expensive.

The story of American manufacturing is one of dramatic rise and gradual decline. After World War Two, US factories churned out shoes, cars, and appliances, employing millions and helping to build a robust middle class.

But as globalisation accelerated in the late 20th Century, many industries moved overseas, chasing cheaper labour and looser regulations. This shift hollowed out America’s industrial heartland, contributing to political and economic tensions that still resonate today.

Shoemaking has become a symbol of these changes. Approximately 99% of shoes sold in the US are imported, mainly from China, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

The domestic footwear supply chain is almost non-existent – only about 1% of shoes sold are made in America.

Pepper Harward, CEO of Oka Brands, one of the rare companies still producing shoes in the US, knows this challenge well. His factory in Buford, Georgia, crafts shoes for brands like New Balance and Ryka.

But sourcing affordable parts and materials in the US remains a constant struggle.

“It’s not a self-sustained ecosystem,” Mr Harward says. “You kind of have to build your own. That is extremely challenging as vendors and suppliers sometimes come in and out.”

To source the foam and PVC for their soles, Oka Brands tried tapping into the automotive industry’s supplier network — an unconventional but necessary workaround.

Oka

OkaFor companies like Keen and Oka, making shoes in America requires patience, investment, and innovation. The question is whether they – and others – can scale production under the protectionist policies now in place.

Mr Harward says there is definitely more interest in local manufacturing because of tariffs, noting that the supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic also spurred greater interest in reshoring. But he is sceptical that tariffs alone will drive a wholesale return.

“It would probably take 10 years of pretty high tariffs to give people incentives to do it,” says Mr Harward. Even then, he believes the industry might realistically see only about 6% of production return to US soil.

As for Keen, plans that began over a decade ago, are coming to fruition. It is the kind of patient investment only a family business can afford.

“We are a private, values-led company,” Mr Perumal explains. “We’re able to do these types of decisions without having to have to worry about quarter after quarter results.”

Still, even for companies who are already making shoes in America, the reality of modern manufacturing is that it is difficult to simply reverse decades of globalisation.

Keen’s new factory is not a signal of a return to the past, but a glimpse of what the future of American manufacturing might look like – one where technology and tradition intersect.

#trainers #cheap #labour