I was first conscious of something rotten in the advertising industry when, standing on a Tube platform, I saw a KFC advert looking back at me. I love KFC. I should be glad to see an advert for KFC. Instead, I was horrified by the poster. “Succumb to the bread crumb,” it declared. I stared at it for a while. “Succumb to the bread crumb”? How could you work on that ad campaign and choose that phrase, knowing that the infinitely better “Succumb to the crumb” was not just staring you in the face but clawing at your hair and screaming into your ears?

It’s hard to escape the niggling feeling that advert copywriting is getting worse. No doubt you have your own personal crusade: maybe it’s adjectives being used as nouns – the trend that had Lexus saying “experience amazing”, or trainer company Saucony declaring, “find your strong”; perhaps it’s the fashion for “I am”, which led brands like Mercedes to launch slogans like “I am Mercedes”. There is plenty to choose from. As brands shriek at you over the noise and AI threatens to take over writing of all kinds, is the art of great copywriting at risk of extinction? Are we struggling to find amazing?

Desperate to discover how a company could plump for “succumb to the bread crumb”, I went straight to the source. “We reached ‘succumb to the breadcrumb’ after a process of creative exploration, and it was one of 400 potential lines we considered for the campaign,” says Monica Sillic, KFC’s chief marketing officer. “We knew we wanted the copy to be punchy, playful and nod to the highly stylised world we’ve depicted in our recent creative. ‘Succumb to the breadcrumb’ stood out to us because it felt memorable and relevant to our breadcrumbed chicken, which is freshly prepared by our restaurant teams every day.” Why didn’t they use “succumb to the crumb”, I ask. “We deliberately chose to use breadcrumb versus crumb because ‘crumb’ could apply to a huge number of other food items, from cakes to sandwiches.”

There is no argument, of course. “Succumb to the bread crumb” is objectively one of the worst things ever committed to print, and a great example of how pedantry kills great copy. Even if you might have thought a focus group could have spotted this problem, brands don’t always use them, and may simply assume that critics don’t fully appreciate the work anyway. (A mini Mandela Effect exists here, incidentally. When I speak to Rory Sutherland, vice-chairman of the UK wing of advertising agency Ogilvy, he is convinced that he saw “succumb to the crumb” somewhere. KFC do not respond to my question about whether they altered the wording in reaction to online feedback, and it seems unlikely that they would have done, given how much they love the version they chose. Sutherland may have seen what his brain dearly wanted him to see.)

“There is a decline in advertising as poetry,” Sutherland says, citing a variety of factors. One unfortunate effect of a more fragmented population having less of a shared cultural lexicon, Sutherland points out, is that it is harder for phrases like “it does exactly what it says on the tin” and “should’ve gone to Specsavers” to have the impact they once did. For this reason, brands often try to go for the jugular. “Tone of voice has sometimes become excessively abrupt,” says Sutherland. “‘Just Do It’ for Nike – fantastic endline – but it gave rise to a whole fashion for what you might call ‘the imperative’ in advertising. I would argue that advertising is there to persuade, not to command.”

Another advert a friend alerted me to was one for shaving brand Wilkinson Sword, in which the reader was assured: “We’ve got your back, face.” The word “face” stood alone, miles away from the rest of the sentence. Given that this was an advert for a razor, the unwelcome – and presumably unwanted – image of someone shaving their back came to mind. I spoke to Dan Watts, who created that advert and a range of others with his team at Pablo London, where he is editorial creative director. Pablo knew they were going up against the mighty Gillette, so needed to give their client something that would make a splash. “You just wanna be noticed and get talked about. And if that means half the people are slagging it off and half the people are loving it, that’s great.”

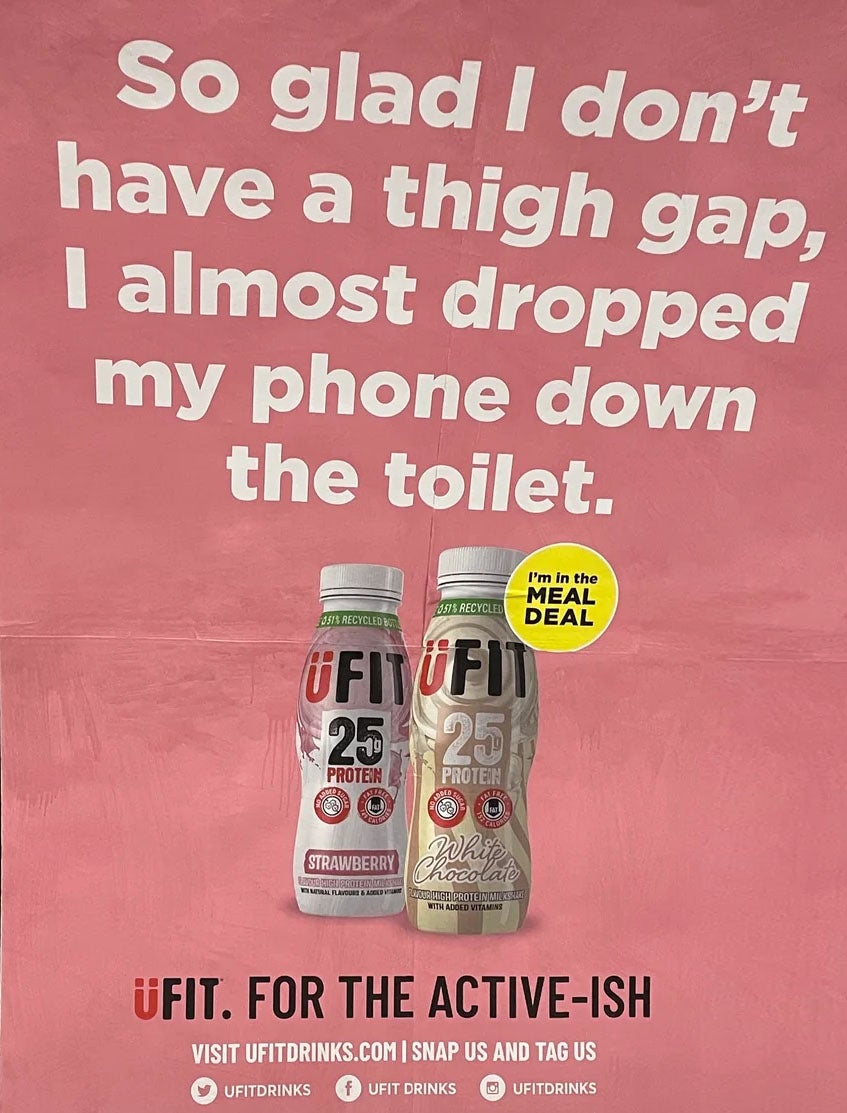

So are these kinds of ads designed to be so unclear that they are talked about solely because of their lack of clarity? Adverts like one spotted two years ago for Ufit protein drinks – “So glad I don’t have a thigh gap, I almost dropped my phone down the toilet” – seem to make that paranoia feel justified. As one Reddit commenter suggested: “I have a theory that Tube ads are intentionally terrible so that you spend longer staring at it trying to work out what is going on.” I certainly stared at “Succumb to the bread crumb” for a long time. Did it make me want KFC more than “Succumb to the crumb” would have?

There is a holy sweet spot, of course, between “Succumb to the bread crumb” and an advert where no one knows what’s happening. “The best press ads always have a degree of obliquity to them,” Sutherland says. “You don’t serve a good advertisement as a hot meal on a plate but you do serve it as what you might call ready to heat. A good ad needs to have that Pot Noodle quality, where most of the ingredients are there but you do have to add boiling water yourself.” Some adverts judge this perfectly. Others – like L’Oreal’s “for make-up that lasts longer than your favourite cheese” – make you so bewildered you’re angry. But, as Watts says, no one remembers 99 per cent of advertising; so is it better to be remembered, however negatively, than leave no trace whatsoever? Many agencies would say yes.

Although it might feel like advertising has become both more opaque and more provocative, Watts doesn’t necessarily agree. He thinks, in fact, that the market has become more risk-averse. “Advertising used to be provocative in the right way,” he says, mentioning the Saatchi and Saatchi campaign for Samaritans which used the line “why you should think more seriously about killing yourself” under an image of a kitchen knife. Today, he says, this advert would be deemed offensive, and a more inoffensive version would be chosen.

Relatedly, copywriting may have fallen down the priority ladder in the industry, being stood on by elements like typography and photography. One of the types of advertising that has died, says Sutherland, is long-copy posters. Brands tended to assume that if people wanted that much information, they could just visit the company’s website. Rarely, of course, can people be bothered to do that. “People have lost faith in the ability of great writing to move people’s hearts and minds,” Sutherland thinks. The erroneous assumption today – conscious or not – is that people don’t have time to read a paragraph of copy.

As well as the indisputable truth that AI can now churn out endless variants on a tagline, putting copywriters out of work in an already saturated market, there is more concrete evidence that copywriters might be less skilled than they used to be. It used to be that you trained as a copywriter or as an art director, Watts explains. Now, “you get creatives, really. Creatives come together and they’re thinking in social [media terms], and they’re thinking in ideas. Nine times out of 10, no one is really brilliant at one thing; they’re kind of good at lots of things. The result of that is that you don’t find that many amazing art directors or copywriters because you don’t really need them in the same way that you used to.” He points to a diminished focus on teaching the art of copywriting, highlighting the 2021 closure of The Watford Course, a creative advertising qualification that condensed everything into a year. “It’s very rare that you need a copywriter to come in and write a beautifully written print ad. That was the job 20, 30 years ago.”

If you believe in the power of great writing, it is difficult to see AI coming up with anything as funny, elegant or charming as “drinka pinta milka day”, “beanz means Heinz”, “you either love it or hate it”. or even, “hi, I’m Barry Scott”. But advertisers will continue to resort to every trick in the book in order to get your attention. In recent years, in the case of Oasis, that involved giving up entirely – or creating a uniquely honest campaign, depending on your point of view: “It’s summer. You’re thirsty. We’ve got sales targets,” read one poster. “Advertising doesn’t work on you. Celebrate this fact with a tasty drink,” read another. The shamelessness of this campaign probably does bring a smile to your lips – something all great copywriters should do, even if they may be struggling more than ever before.

#Advertising #copy #worse #deliberate